Perhaps it doesn’t come as a surprise that we all have unique driving styles. My father is a calm, sometimes even slow driver. My mother is more temperamental in her driving ways - always cutting the line where she can (this was a highly useful skill when we were late to school). When I close my eyes, I can immediately tell whether my mother or father is behind the wheel.

But so can anybody - using in-vehicle logs. Turns out that these driving styles can translate to bits and bytes that our in-vehicle sensors record.

In-vehicle sensors

There are a number of systems built in our cars for various purposes - to regulate emission, to optimize engine performance or to log and detect malfunctions. Think of your dashboard for example - you can see your speed, consumption and RPM all at a glance! The data required for these comes from in-vehicle sensors. This data is converted and processed by ECUs (Electronic Control Unit), which are essentially small computers inside our cars. The ECUs communicate with each other through the so-called CAN-bus (CAN - Controller Area Network).

The CAN-bus whisperer: OBD dongle

The data sent over the CAN-bus can be easily captured. For example, so-called ”insurance dongles” (or On-Board Diagnostics dongles) can collect and send in-vehicle sensor data to insurance companies. They use this information to give you discounts for example, if you drive safely.

Another similar approach to lowering insurance premiums is using telematics data, as described here. The biggest difference however, is that telematics data are currently subject to data protection laws, unlike CAN logs.

The OBD dongles connect to the ODBII interface of the vehicle. These devices are not expensive at all (prices start at 10$), and can come with mobile apps so you can look at your data from your phone!

In some cases, we cannot access CAN logs directly through an OBD port (or at least not all parts of it). There is usually a gateway regulating access to these data.

Even though CAN-bus data can be readily accessible (and not encrypted), the interpretation of the messages is still a challenge. There is no global standard, and the structure of the messages varies from manufacturer to manufacturer. Without the cooperation of manufacturer, it is hard to reverse engineer these messages… but not impossible! If you want to know how to do it using machine learning techniques, check out my talented colleagues’ paper (Lestyan et al., 2019)!

Driver fingerprinting

So what can we do with the obtained CAN-bus data? Turns out, that we can use it to determine who was behind the wheel.

How it works

Driver fingerprinting or driver re-identification uses the data collected from the CAN logs (called traces) to correctly identify drivers. From these traces, we can extract the data from one sensor to obtain a time series (measuring speed for example).

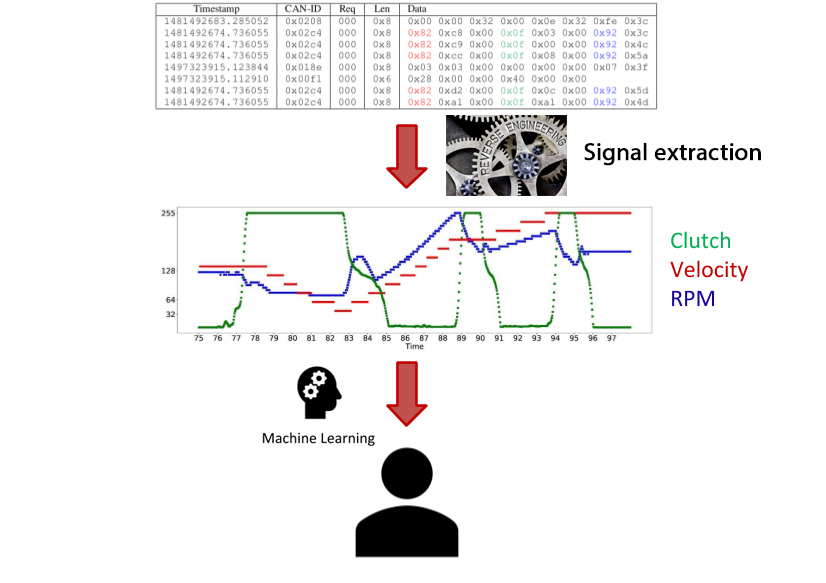

The input of such a model can consist of multiple time series, like in the example image below. However, to obtain these time series, first we need to reverse-engineer them. Then, we can use Machine Learning to make predictions on the driver’s identity.

For my 2018 Scientific Students’ Association paper I used the measurements of 5 sensors (namely brake, clutch, gaspedal, rpm and speed). Brake, clutch and gaspedal sensors measure the position of the respective pedals. As for the rest: rpm records the revolutions per minute and speed measures the vehicle’s speed. I was also able to work on data collected from 33 drivers, whereas state-of-the-art driver re-identification papers only published results on models that had to distinguish 2-15 drivers. My model achieved a 66% mean accuracy, given a mere 10 second trace as input!

One might think that this time-window can be pushed down even further - theorizing that the distinguishing part in everyone’s driving could be the part where they accelerate or shift gears, which is about 2-3 seconds long. However, when driving in a city there are a lot of situations where one must stand still (in morning traffic, in front of a stoplight, or while letting that old lady cross the street). Related work suggests that all the information needed to identify a driver can be obtained from the measurements of a single turn. This confirms the intuition that someone’s driving can be quite accurately distinguished based on how they slow down, switch gears and accelerate.

After writing this paper me and my colleagues were motivated to extend this research by eliminating the first step: reverse engineering the raw data.

Driver re-identification on raw data

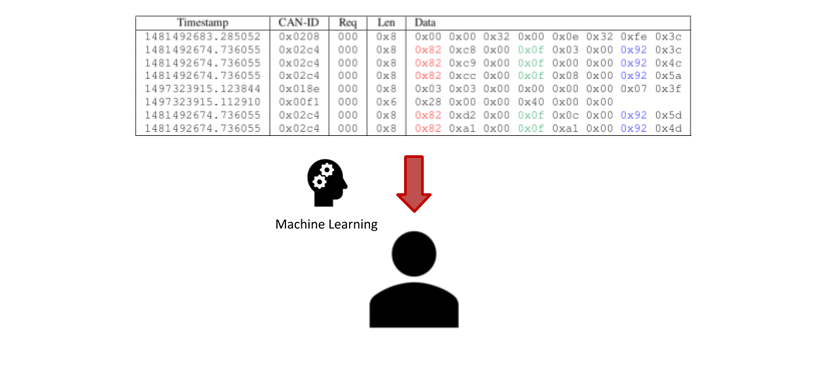

In our paper titled Automatic Driver Identification from In-Vehicle Network Logs we demonstrated that it is possible to achieve the same results without having to reverse engineer and pre-select signals from the CAN log.

We collected 72 time series from unknown sensors and trained a Deep Learning model on each of them. Not all time series were equally good inputs for the re-identification task, which is why we combined the top-10 performing classifiers into one mixture model. We achieved a mean accuracy of 75-85% for CAN traces whose length varied between 20 and 120 seconds.

Great! Acquiring an OBD dongle that can read CAN logs is not only cheap, it turns out you don’t have to understand the data to build a working driver-fingerprinting classifier with it.

Privacy implications

So now that we know that our in-vehicle data could potentially identify us, why should we protect it? I mean, aside from well-wishing insurance companies who give us discounts, who could possibly get our data?

Except if… car companies were motivated to sell CAN logs to 3rd parties. And currently they could do so. Without our consent (because it is not considered to be personal data as of yet). Uh-oh.

Driving data: the car industry’s new cash cow?

Many sources suggest the lucrativity of driving data – McKinzey&Co, a management consulting firm, estimates that ”data from connected cars will be worth up to $750 billion by 2030”. Companies are already preparing for the market for data from cars, which is expected to be even bigger than the market for the cars themselves acording to this Forbes article.

Future ideas include selling data to mapping firms looking to provide more accurate traffic information, or selling consumption-related and other statistics to operators of larger vehicle fleets. And if driver identification is possible, it opens all kinds of doors. For instance, you can use driver identification to notify you any time someone else is driving your car. Or your car could “memorize” your driving fingerprint, and adjust your seat, and radio to your liking as soon as you turn the corner. Neat, right? But wait, something is missing from the list - the biggest cash-grabber of them all: ad revenues. In the hands of 3rd party advertisers, our cars could be yet another gateway to personalised advertisements.

Just like with any other personal information that could potentially identify us: using such data should require our explicit consent!

GDPR and awareness

Because of how new these findings are, it is still unclear whether drivers are completely informed about the wealth of personal information that their CAN logs potentially reveal. Hopefully this post was an eye-opener to the inevitable future where even our driving data will be on the market.

Although car companies stress that the collected network logs are “anonymized”, the proper anonymization of such high-dimensional data is notoriously difficult in practice without significantly degrading accuracy (Aggarwal et al., 2005). Even aggregated metrics aren’t always completely safe (Dinur and Nissim, 2004). The feasibility to identify (and/or profile) a driver means that CAN logs are indeed personal data and, as such, are subject to the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) as of 25 May 2018. It is a fundamental duty of companies handling such data to adequately inform drivers and protect their personal data. Failing to do so does not only ruin customer trust, but can also result in a fine up to 20 million Euros.

Closing thoughts

We have seen that it is fairly easy to access this data, and will probably become even more accessible in the not-so-distant future of connected vehicles.

Massachusets has voted (Nov. 4th, 2020) on standardizing access to car data (to extend the state’s right-to-repair law)! This could set a standard for the vehicles to come…

We have also seen that even without the reverse-engineering of the logs, identifying drivers is still possible. Turns out, our phones aren’t the only devices that store and/or process information which could potentially identify us. :)

I don’t know what driving fingerprint I posess, but I hope I can eventually get the best from both of my parents: my father’s calm (but ultimately safe) driving and my mother’s mad parking skills!

A special thank you to the following people who have provided me with useful feedback and suggestions: Gergely Ács, Andris Gazdag, Ferenc Huszár and Viktor Remeli.